SEVEN DEADLY / SEVEN HEAVENLY:

New Orleans Eccentrics

extreme hubris or self-confidence.

Before being assassinated in 1935, Huey P. Long, Jr. was revered by the masses as a champion of the common man and demonized by the powerful as a dangerous demagogue.

Nicknamed “The Kingfish,” Huey served as the 40th Governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932, served as a member of the U.S. Senate in 1932, and became an outspoken populist who denounced the rich and called for “Share the Wealth.”

Long’s leadership was strong and charitable, but his prideful dictatorship left him with a corrupt legacy despite the local monuments in his memory. Huey P. Long remains a controversial figure in Louisiana history, both politically and socially.

intense desire.

Ill-famed dens of erroneous behavior. Pleasure palaces. Cathouses and honkytonks. Basin Street was a scarlet artery threading New Orleans where a legalized area for prostitution reigned from 1897 to 1917. Red lanterns hanging on doorways indicated Storyville’s brothels, creating a red-light District where curious men could sample octoroon and quadroon women employed by madams such as May Baily, Kate Townsend, Lulu White, and Josie Arlington.

The Arlington, a tulip-domed cupola with bay windows, fireplaces, oil paintings, and fine wine, was famous for its opulence as much as its depravity. Live sex “circuses” and fetish specialists were featured nightly, and Josie Arlington went to her death the shrewdest, most prominent madam in Storyville’s history.

over-indulgence.

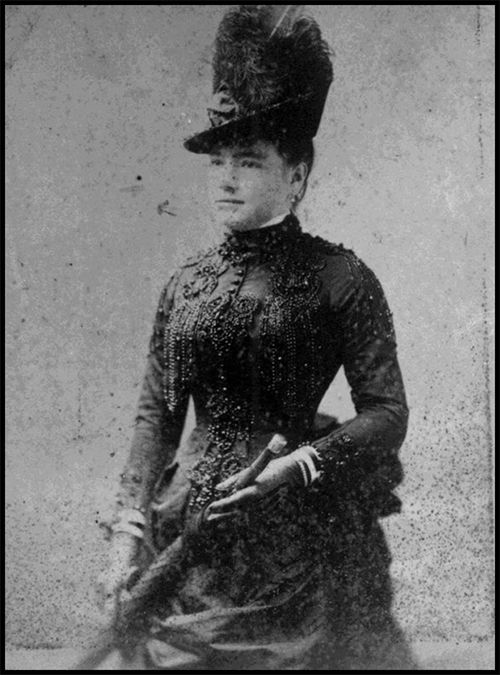

From petty thief in the French Quarter to gangster mastermind for the mob, Carlos “The Little Man” Marcello ran New Orleans in the 1940s. Marcello was the boss, the godfather, the Mafioso who controlled an illegal network of gambling in Louisiana while providing muscle and skimming Las Vegas casinos.

During investigations of John F. Kennedy’s death, Carlos and his crime family were implemented in plotting the assassination. Convictions were never made.

Before his own death by a massive stroke, Carlos Marcello and “Diamond Jim” Moran owned an Italian-Creole restaurant “La Louisiana” in the ‘50s to the ‘80s where the notorious mobsters ran their organized crime. The newly opened bar “21st Amendment at La Louisiane” pays homage to the foregone mafia era.

covetousness of material wealth.

Deep in the swamps of lower Louisiana, the Mississippi River dumps into the Gulf of Mexico leading to the Atlantic Ocean. This watery gateway offers passage to America for cargo ships on their European crossing. During the 18th century, a cluster of islands called Barataria was perfect for a band of buccaneers, led by Jean Lafitte, to set up a pirate haven, pillage passing ships, and smuggle the stolen goods into the city of New Orleans to sell for profit.

Jean Lafitte was king of Barataria Bay, and although he never saw himself as a pirate but rather a privateer, his charming mannerisms and handsome grace could never mask the greed beneath his hat and plume. Regardless, the city still honors Lafitte for fighting in the Battle of New Orleans against the bloody British.

spiritual or emotional apathy.

From the exterior, the mansion at 1140 Royal Street appears to be a lavish home filled with expensive décor, yet it is haunted by hundreds of ghastly souls once tortured, mangled and murdered inside the hidden attic by a madwoman.

Marie Delphine LaLaurie was a socialite who threw parties of gaiety for the New Orleanians who admired her wealthy family. In 1834 a kitchen fire broke out, and the firemen in rescue found a horror scene upstairs. Slaves, half alive, half dead, laid bloody in filth inside Madame LaLaurie’s makeshift torture chamber where she had performed bodily experiments and mutilations. Delphine fled the city, escaping an angry mob with hanging ropes, and never brought to justice.

The LaLaurie mansion remains the most haunted house in New Orleans.

rage. violence. anger.

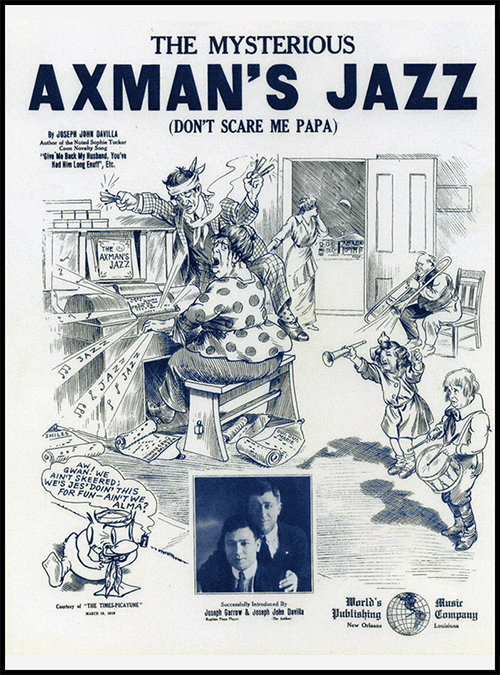

He was “Jack the Ripper” of New Orleans. He terrorized the city for over a year in the early 1900s. He killed with the victims’ own axe. No one knows why. Suspect of the mafia’s involvement arose. Sadism? Insanity?

After at least eight victims found themselves hacked to death during the Axeman’s killing spree, the only motivation that can be theorized is the killer’s attempt to promote jazz music. He wrote a letter to the newspaper saying he would kill again at midnight but would spare anyone listening to a jazz band. That night, the dance halls were filled with nervous patrons, and there was not one murder. There were no screams in the night, only the sounds of early jazz.

To this day, no man has been apprehended for these heinous crimes.

insatiable jealousy.

Some New Orleans characters are so eccentric, they practically leap off the page. Blanche DuBois, penned by Tennessee Williams in 1947, steps off the streetcar onto Elysian Fields in search of her younger sister’s house. Blanche, once an aristocratic southern belle living in her family estate Belle Reve, is now penniless and forced to live alongside Stella’s brutish husband, Stanley.

With resentment for Stella’s abandonment of their family and repulsion for Stanley’s blue-collar lifestyle, Blanche watches the couple in secret envy of her sister’s primal love for her beastly husband. Their passionate desire is a mere reminder that Blanche, in her own immortal words, has “always depended on the kindness of strangers,” rather than the earnestness of marital love.

the modest giving of respect.

Haitian rituals of Louisiana Voodoo conjure images of twisted mysticism and cryptic iconography. In New Orleans, one name seems to attach itself to this esoteric religion: Marie Laveau, the Queen of Voodoo.

But Marie Laveau was not an evil practitioner sacrificing animals in ritualistic devil worship. Although her life remains much of a mystery, it is said she lived in the French Quarter on St. Ann Street and worked as a hairdresser. During the great Yellow Fever epidemic, she aided as a nurse and spiritual healer, and after the Great Fire of 1788, she helped rebuild the St. Louis Cathedral where she frequently churched. Marie Laveau’s legendary magic may never show evidence of having existed, but she remains a spiritual influence on the city.

abstinence and purity.

Born into a segregated existence of left-hand marriages known as plaçage, Henriette DeLille was the daughter of a free woman of color who grew up in a world of racial division and social boundaries. Rebelling against her upbringing of becoming a quadroon mistress, Henriette formed a congregation of nuns in 1842 and furthered their ministry as the Sisters of the Holy Family.

The Sisters purchased the old Quadroon Ballroom and converted it into a convent where St. Mary’s Academy became the first Catholic secondary school for colored girls. Henriette DeLille followed her spiritual calling, and today the Academy and the Sisters of the Holy Family continue the mission of the order with thirty-seven schools, two orphanages, and a home for the aged.

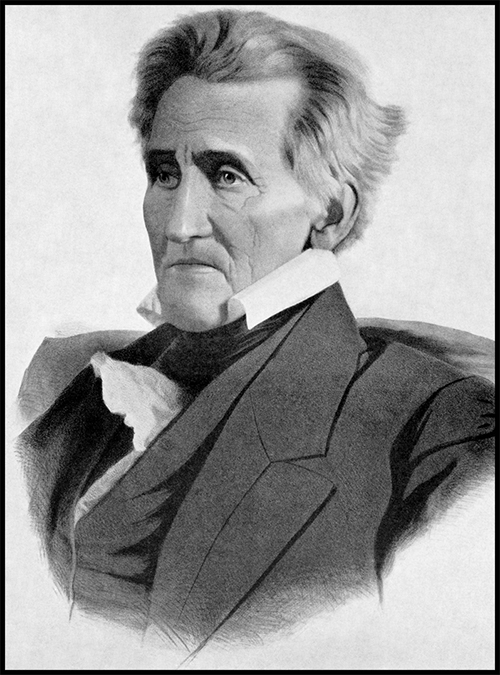

justice and honor.

Before becoming the 7th President of the United States, the hands of General Andrew Jackson were stained with blood. He dueled to the death, he was a wealthy slaveholder, and he teamed with an army of pirates in order to defeat the British during the War of 1812 at the Battle of New Orleans in Chalmette.

But “Old Hickory” was a Tennessee gentleman whose love and devotion for this country was insurmountable. “I will die with the Union,” he always insisted. He is honored as the hero of New Orleans for taking command of the defenses, and his equestrian statue stands in the center of Jackson Square, built in his honor and always remembering the strength of a man “as tough as old hickory wood on the battlefield.”

benevolent generosity.

Money and murder sometimes go hand in hand. For the Baroness de Pontalba, a wealthy aristocrat who was shot four times at point-blank range, it certainly seems true. After her father-in-law attacked her with a pair of dueling pistols and committed suicide, she survived and used her inherited millions to become a successful real estate developer in both New Orleans and Paris, France.

Inspired by the Place des Vosges in Paris, the red-brick townhouses surrounding Jackson Square were Micaela’s own construction and design, and if you look closely at the ironwork decorating the balconies, her initials of “AP” are carved into the center of cast-iron. The Pontalba Buildings cost more than $300,000 and offer the benevolence of lavish hospitality and genius in architecture.

steadfast and diligent ethics.

After the French-founded city of New Orleans was sold to Spain, a Spanish Capuchin friar named Antonio de Sedella was sent to the city as an official of the Spanish Inquisition. Commonly called Père Antoine, the friar was not an enthusiastic inquisitor, and eventually he was named pastor of the St. Louis Cathedral. He dedicated himself to the city’s prisoners and slave population, and he worked tirelessly to free women of color and their children.

For many years he served as parish priest and was dearly loved among the poor people of New Orleans. After his death, it has been said he has been seen in the alley alongside the Cathedral which was named in his honor. His ghost walks silently in robes, reading his breviary without looking up at passersby.

peaceful grace and forgiveness.

Much of the heritage in the city of New Orleans originates from France. Art is among this strong heritage. It is a city where artists blossom, such as young Edgar Degas who lived briefly with his Creole uncle on Esplanade Avenue where now the Degas House B&B is open to the public for tours and events.

Although considered a founder of Impressionism, Degas preferred to be called a realist. His work of paintings, sculptures and drawings convey the most realistic color and form of contemporary life. He focused on backstage ballet rehearsals, portrayed everyday life of milliners and laundresses, and composed tensions between men and women. Although realistic, his paintbrush was graceful in its psychologically poignant portrayal of turn-of-the-century life.

compassionate loyalty.

Escaping the guillotine by moving to a frontier town named New Orleans in the early 19th century, Count Joseph de Roffignac became mayor of the city from 1820 to 1828. During that time, Roffignac spearheaded the early planning of levee construction along the Mississippi River, paving the first cobblestone streets in the French Quarter, and most significantly, introducing street lighting to the city by illuminating the lantern-carrying Quarter with gas lamps in 1821.

Since then, Roffignac’s name has been coined into a cocktail which embodies the suppleness of Cognac sparked by fresh raspberry and can be ordered at any local watering hole. Count Joseph de Roffignac gave New Orleans levees, cobblestones, and streetlights. That’s a life worth lifting a drink to!

In a city filled to the brim with juxtaposition, New Orleans is a complex landscape of violence and religion, of sinister acts and saintly gifts, of brutality and compassion side by side. With street names literally altered between historic saints and legendary sinners, the city's heritage is a cultural line up of eccentric personalities who have garnered lives filled with mainly good or mainly bad influences. Here, we like to say, "sin tonight; church tomorrow." These characters are the Adams and Eves of original sin and sanctity.

SITE CURRENTLY UNDER CONSTRUCTION.

• • •

Please pardon our pixel dust!

SITE CURRENTLY UNDER CONSTRUCTION.